The efforts of 488 Squadron against the odds at a crucial time in history of the British Empire have gone largely unrecognised - Last stand in Singapore - Graham Clayton

The surrender of Singapore was a catastrophic loss for the allies in the second world war

New Zealand’s very first air force fighter squadron, 488 Squadron of the RNZAF, was posted to Singapore just three months before it fell. This dynamic bunch of Kiwi fighters helped delay the enemy’s advance as best they could with severely limited resources — and a good measure of Kiwi ingenuity. But the cost was high, and many would never discuss their experiences, never completely recover from that traumatic time.

Bert Clayton’s war started at 2.30am Singapore time on 8 December 1941.

With a crash that had him instantly standing beside his barracks bed at Kallang like a stunned mullet. Just a few kilometres away the Japanese were bombing the port of Singapore. What had woken Bert was the rattle of the anti-aircraft fire that had started as the bombers made their initial run over the city. When he realised what was happening he and the others vacated their billets and sprinted for the foxholes they had dug. This was to be the pattern for them for many more nights to come. Bert Claytons experience of the first day of conflict with Japan

Flight Lieutenant John Mackenzie and Sergeant Jim MacIntosh took off and headed towards the last reported position of Force Z.

They knew by the co-ordinates given that they would be heading out to sea and the first inkling of a disaster began to sink in.

Until much later in the day they were not to know its extent. Of course, they were much too late. Four separate patrols of two aircraft went out during the day, but all they could do was provide air cover for the destroyers picking up survivors from the Japanese raid. The sea in the area was littered with debris and survivors waiting to be picked up by escorting destroyers. The disaster that had taken place was the forerunner of what was to come for the island of Singapore.

488 Squadron was put on standby to provide aircover for Force Z but the request came way to late

The New Zealanders find themselves up against a superior enemy and take heavy loses

Because the Buffaloes’ top speed was only marginally superior to that of the bombers they were chasing, when they were overtaken it was almost impossible for the New Zealanders to get into an attacking position, and thus there was little they could do to defend themselves against the bombers’ superior tail-gun defence. As a result, in the first two days of active service seven aircraft were lost from the original 21.

Squadrons first Kill, January 15th

Sergeant Eddie Kuhn recorded 488 Squadron’s first kill on the same day, sending a Japanese Type 97 fighter crashing to the ground. Bert saw the battle from Kallang and he remembers watching from a distance three aircraft in succession diving steeply towards the ground. Two crashed but the third pulled out of the dive at the last minute and returned to the fray. Bert later learnt that the first two were Japanese fighters, the third being Geoff Fisken, a New Zealander with 243 Squadron who followed his victims all the way down to make sure of the kill.

Squadron takes loses, 19 January 1942

On 19 January the squadron lost Pilot Officer Jack McAneny and Sergeant Deryck Charters. McAneny was shot down and killed just out of Muar township on the west coast of Malaya. He was 19 years of age. Charters survived after parachuting from his stricken aircraft and was taken prisoner by the Japanese. He was originally listed as missing believed killed, but the International Red Cross later informed his family that he was in a POW camp in Thailand where he died of dysentery on Christmas Day, 1943.

Shortly after the last raid of the day, a Blenheim aircraft of 27 Squadron, flown by a New Zealander, tried to land at Kallang with no brakes. The only clear and undamaged ground was around where three surviving Hurricanes were parked.

Wilf Clouston shouted out, ‘Here comes a bloody idiot,’ drew out his revolver and said he would ‘shoot the bastard if he as much as touched one of the parked aircraft’. Fortunately, the Blenheim missed all three by the closest of margins and the pilot taxied his aircraft away, blissfully unaware of what his fate could have been.

Bert Wipiti and his friend Charles Kronk view a down Japanese fighter

Maori Sgt Bert Wipiti RNZAF Singapore checking out an Oacar he shot down Singapore 21st January 1942

OBLITERATION OF THE AIRFIELDS AND AIRCRAFT. Late January 1942

The situation was getting desperate on Singapore, with constant shelling and bombing. The Japanese were now consolidating in Johore just a few kilometres from the island. On Saturday, 31 January, the last of the retreating British troops crossed the causeway onto Singapore Island and army sappers blew a breach in the causeway to slow the Japanese advance.

All around the island explosions could be heard, particularly from Johore and the naval base at Sembawang, and it was obvious now to all those at Kallang that a ‘scorched earth’ policy was being adopted and units everywhere were firing their fuel and explosive dumps. The end of Singapore as a British outpost was obviously very near.

By February the pilots of 488 squadron were withdrawn to Batavia, Java leaving the ground crew alone to service other squadrons aircraft.

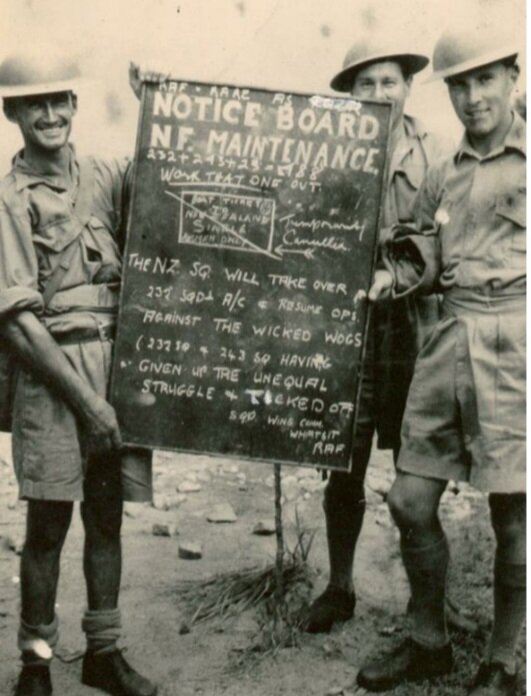

The indomitable 488 groundcrew

The squadron at Kallang continued to operate and not at all unsuccessfully and curiously, as distinct from elsewhere, the ground staff was by all accounts pugnacious. With the Japanese already on the island and with all the other airfields occupied by the Japanese or under attack, they found a sense of purpose which allowed flying to continue until February 10th 1942.

Sergeant Terence Kelly, 232 Squadron on the Nz ground crew

The last plane

The sole Buffalo by this time had fired up and was trundling down the runway. Donahue was helped by two of the groundcrew who he knew would be left to face the Japanese.

Looking back for one last time, my memory is of a bright green little country, resting on the edge of the bluest sea I’d ever seen, lovely in the morning sunlight except where the dark tragic mantle of smoke ran across its middle and beyond, covering and darkening the city on the seashore. The city itself, with huge leaping red fires in its north and south parts, appeared to rest on the floor of a vast cavern formed by the sinister curtains of black smoke which rose from beyond and towered over it, prophetically, like a great overhanging cloak of doom. Art Donahue on the fall of Singapore 1942

As Art Donahue flew away, below him the groundcrew of 488 Squadron were left to face whatever was to come their way. They had no chance with the Japanese within sight of them, and they must have felt the end for them was near.

What is reputed to be the last Allied photograph taken from the air over Singapore before the surrender to the Japanese forces.

Ground crew make it out of Singapore

As Commonwealth units bravely held back the Japanese advance the ground crew of 488 squadron were ordered to the port to depart on Empire star.

They came to a crossroads at one stage and waited while a party of Japanese soldiers carrying rifles crossed in front of them. The soldiers appeared not to notice them so they turned the truck and headed off in a different direction. Further up the road they spotted more groups of Japanese all heading in the same direction. They could only keep going and in the confusion they were not challenged.

As they reached the docks, The port area was a shambles. Most of the city seemed to be afire, the flames reaching skyward; fire-fighting services or intact water mains were simply non-existent. Great clouds of black smoke covered the sky, and out of that sky continually came Japanese dive bombers, completely unopposed, bombing and machine-gunning the crowded streets.

They reached the vessel just on dusk and somehow, probably due to the influence of their late CO, the now departed Wilf Clouston, were allowed to board the already overloaded ship.

The New Zealand ground crew boarded the Empire Star which was the last of the so-called big ships left in port on 11 February 1942.

As the ship left the wharf those on board must have been thankful that they were not to share the fate of those left behind, but they still faced the uncertainty of whether they would reach their destination in safety.

The mad dash to freedom

The flotilla was guided out of the channel by the escorting destroyers heading south towards the Durian Straits. The trip down through the straits was uneventful but as they reached the southern exit things started to happen. Japanese bombers soon hit the convoy hitting Empire star 3 times. In this first attack by the dive bombers, according to Captain Capon’s official report, 12 military personnel were killed and a further 17 military and ship’s personnel were severely injured. The bombing runs continued until late in the afternoon as successive waves of bombers of up to 57 aircraft tried to sink the ships. Each able-bodied man on the crowded decks fired into any of the low-flying aircraft, with the civilians and nurses down below also taking the empty rifles, reloading them and passing them back up. The Lewis machine-guns were tied to the ship’s rail with rope to provide steadier support.

The Empire Star was one of only two vessels that were not sunk that day out of 16 ships that had left the port with them.

New Zealander Bert Clayton found himself with many others desperately trying to put up sufficient firepower to bring down their attackers.

On the 13th of February the ship came across the Japanese invasion force for Palembang, Sumatra but out of either share luck or the Japanese not seeing the ship as a threat they passed by. Either way, it was one of the quirks of fate that once again helped the men of 488 Squadron to survive.

The Empire Star finally arrived in Tanjong Priok, Batavia, the port of what is now Jakarta City, around 6.15 on the evening of 13 February 1942. They had started out in a convoy of ships but one by one these vessels had been sunk, run aground, intercepted by the Japanese or simply disappeared without trace. It has been estimated that over 70 vessels carrying up to 5000 people that left Singapore did not make it to safety. The official casualty count on the Empire Star was 14 killed and 17 severely wounded, but many of the survivors claim many more were killed.