Ray Lawrence a machine gunner crossed from HMS Hereward to another ship tied up to the wharf, Suddenly a air raid siren wailed. He immediately dived among some crates for cover. When the All Clear sounded, he found the crates were marked, Handle with care. “High Explosive.”

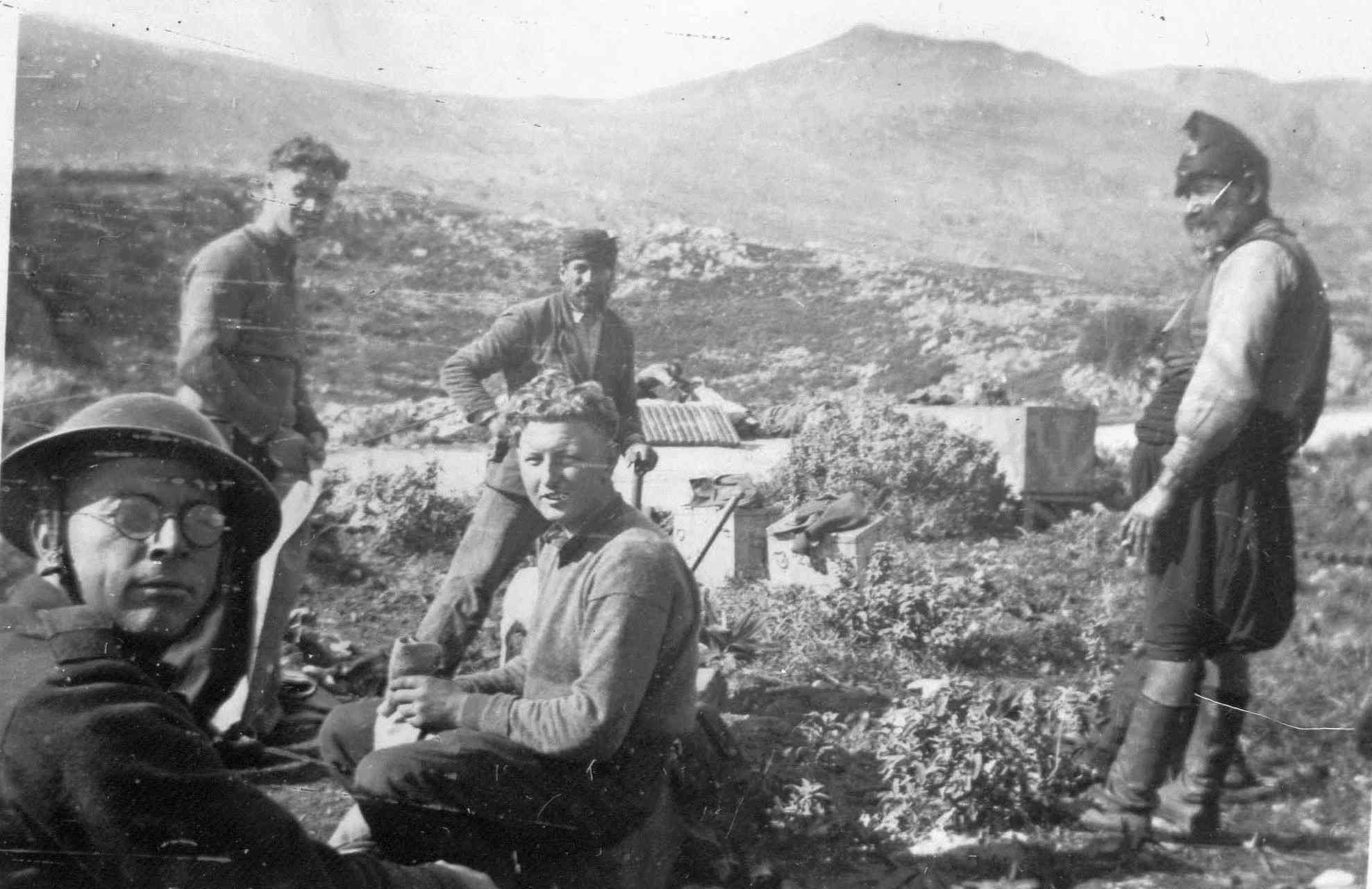

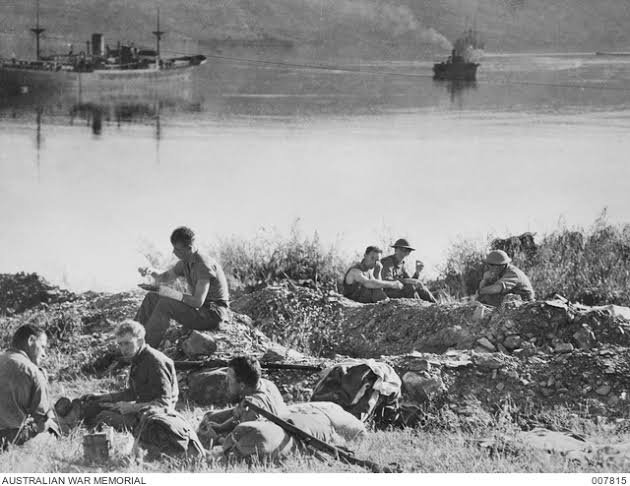

Welcome to Suda Bay

Men arrived on Crete with few arms and fewer supplies. There were drivers without trucks, artillerymen without guns, signallers without wire. These men, of reduced military value when parted from their specialist equipment, had to be fed and clothed like the rest.

Situation of Crete, 1941

General Freyberg takes control of all allied units on Crete

The New Zealanders had nearly a month on Crete before the blow fell. They were given an area to defend that stretched from Canea, a town on the northern coast, westward along the shoreline to the Maleme airfield—a strip about ten miles long. It was laced with ridges and streams running from the central mountains to the sea, clothed with olive trees and vines, with only one substantial road that ran parallel with the northern coastline.

‘The decision has been taken in London that Crete must be held … it can be held only with the full support of the Navy and Air Force. The air force on the island consists of six Hurricanes and seventeen obsolete aircraft. Troops can and will fight but, as the result of the campaign in Greece, are devoid of any artillery and have insufficient tools for digging, little transport, and inadequate war reserves of equipment and ammunition. I recommend that you bring pressure on the highest plane in London either to supply us with sufficient means to defend the island or to review the decision that Crete must be held.’

Major-General Freyberg

After the battle of Crete, German aircraft raided Crete daily

New Zealander Roy Coates during a German air attack lay flat on his stomach, Looking upwards as two Messerschmitt’s sprayed the area around him. “I could see it all, what was happening,” he says “Bill Somerville, who was next to me, tried to get a slightly better view. He lifted his head a bit more, and I just started to say “Pull your head in” and he suddenly slumped against me. I half turned around and it had just ripped his throat right open. He was dead. I didi’t think you could die so quickly.

Invasion Begins 20th May 1941

It began like most other days. At six in the morning the planes were overhead, bombing and strafing, but this morning there seemed a greater intensity about it. Yet when this bombardment fell away, and allowed the troops to begin their breakfast, there was little to suggest that this day would be different from the others.

Maleme airfield came in for special attention and around the perimeter the intensity of the bombing was so severe that men who had gone through the artillery barrages at the Somme stated later that this was more terrible. Further afield, from out over the sea, the roar of an approaching air armada beat upon the ears.

Black dots suddenly fell from the bellies of the low-flying planes. In an instant the dots were blossoming into parachutes, hundreds upon hundreds of them, swaying swiftly earthwards, filling the sky with their different colours. There seemed then a moveless pause, as if the defenders were transfixed by this amazing sight. But only for a few seconds. There was no long delay as the parachutes wafted down.

There was hardly time to aim and fire, but then the crackle of rifle-fire began, swelled into a chorus, Bren guns added their chatter, and the bodies of paratroopers began to twist and squirm as they came near the earth.

New Zealander Sandy Thomas said the Parachutists looked like “Little jerking dolls whose billowy frocks of green, yellow, red and white somehow blown up and became entangled in the wires that controlled them'“

Colin Farley said they were “white handkerchiefs being let go out of a carriage window.”

But those who fell close by the New Zealanders learnt a lesson that Hitler never repeated during World War II.

Of 136 paratroopers who landed near 18th Battalion only two survived.

The enemy landed 10,000 men that day. By nightfall only 6000 remained active.

A wave of paratroopers swung to earth by the lines of an engineers’ unit. Their descent was watched by an infantry headquarters not far away. ‘Ring up those engineers,’ the infantry C.O. ordered sharply. ‘Can’t expect sappers to deal with paratroops. Tell them we’ll send over help.’ Back came the reply. ‘Thanks, but don’t bother. They’ll all be dead before you can get a man over here.’ The engineers were almost true to their word. On one German body was found the unit nominal roll, showing that 126 men jumped that day into the teeth of the belligerent sappers. A mere fourteen escaped the fate of the 112 others.

During the heavy fighting around Hill 107 the Māori Battalion come across Germans paratroopers in the dark who yelled out “We surrender” then throwing a grenade. The incensed Maori charged with bayonets, a few standing back and doing hakas, 24 Germans were killed.

Maleme airfield 20th May 1941

‘Cover me!’ he said shortly. They knew what to do. They had practised it often enough. The men went to ground, picking their cover, and began firing steadily into the area where the ‘chutes lay. Upham went round the flank, moving quickly forward and out of sight. Five minutes later they heard a flurry of shots. Then silence. He was soon back, appearing suddenly out of the olive trees, swinging a German helmet in one hand. ‘She’s right now,’ he said, his voice sharp with excitement. He didn’t tell them any more.

Charles Upham (VC) experiences during the battle around Maleme Airfield

Critical mistake made

By late afternoon the Kiwis around the ’drome were out of touch with their own headquarters and with one another. Battalion and Brigade Headquarters further back gained only a confused and pessimistic view of the situation.

With the Germans gradually gaining a foothold on the vital airfield, counter-attack was imperative.

When finally the word came through to Brigadier L. M. Inglis,—‘Counter-attack not permitted’—his Brigade Major leapt up and shouted: ‘Then we’ve lost Crete! We’ve lost Crete!’ Inglis snorted: ‘You don’t need to tell me that.’

Night came. There was no communication with the men on the airfield. German airborne troops seemed to be in nests and patrols everywhere. We had had some sharp losses. There was to be no counter-attack on the ’drome. So the vital decision was taken withdraw from the airfield.

During the day more German paratroopers landed unexpectedly over the 28th Maori Battalion. Many men were killed in the air or while undoing their harness. An Australian solider recalls “The Māori troops down on the left go into a bayonet charge and the noise of their yells and the Germans screaming chills the blood.”

Maleme Airfield pictured above full of German aircraft

“What would have happened,’ Inglis asked, ‘if I had been permitted to counter-attack you that afternoon?’ Student said: ‘If you had done so, I could not have held Crete. You had knocked me about so much that day, particularly my paratroops, that I could not have resisted a counter-attack. After the way you smashed up my units on landing, all day long we waited for your counter-attack. We feared it, we thought it must come, and were amazed that it didn’t.”

Lindsay Inglis spent an afternoon with General Student, the German commander of the invasion and spoke of the moment he lost Crete

Crisis at Maleme

The next day, 21st May 1941, saw the Germans massing reinforcements into Maleme. Some of our guns still played on the airfield and on the nearby beaches, where troop-carriers attempted landings; but by afternoon planes were landing on the ’drome at the rate of one every three minutes. With Maleme secured, the German plan would be to advance east to Canea, rolling up the New Zealanders on the way.

There was sharp fighting with our advanced battalions, but the enemy made little progress against the defences. Smarting under his heavy casualties of the opening day, he was content to concentrate on building up men and supplies, probing forward where he could.

During the day it was belatedly realized at Force H.Q. that all would be lost unless Maleme were recaptured. A counter-attack had to be made. But by day the air strafing was insuperable and prohibited practically all movement. So the counter-attack on the airfield would have to be a night show.

New Zealanders Counter Attack

20th and the fiery Maori’s of the 28th were picked for the counterattack.

No forward move could be made, however, until an Australian unit arrived by truck from further east, took over the 20th’s defence positions, and handed over its vehicles to the 20th to take the men forward to the start line.

Unfortunately the Aussies who were due to replace the New Zealanders were delayed due to enemy bombing and strafing. It was half past three in the morning before the advance started.

‘We knew then that we would never reach the ‘drome before dawn,’ he said. ‘We knew there were mine-fields laid by our own troops which we would have to get through, but there was no time to get information about them. But we knew the attack had to go in. The fate of Crete depended on it. There would not be another opportunity.’ James Burrows on why he decided to launch the counterattack after being critically delayed.

New Zealander Jim Burrows recalls. “The period waiting for the order to advance was one of inertia driven by fear. I knew that I would never get moving, he says. I was terrified. Then a voice came along the line, Fix bayonets, fix bayonets. Click, click, click, click. The most wonderful sound. And suddenly all the fear left and I felt so strong and almost intoxicated.”

Each man strained his eyes ahead, peering into the darkness, watching the shadowy outlines of the country gradually unfolding. Four miles of this before they reached the Drome. Each man glancing to his right and left, keeping spaced out from his mates, hoping against hope that it wouldn’t happen, knowing for sure that the time would come, sooner or later, when flame and death would suddenly, without warning, shriek at him.

Then sharply through the night came the first rifle-shot, not a hundred yards away, then another, and another, and suddenly the air was filled with the sound of it. Machine-guns broke into their chatter, and through the darkness lines of tracer came weaving in fiery patterns.

The New Zealanders surged ahead. But they found now, and as the attack continued on and on, that the Germans had spread themselves right through this country, with posts established behind trees, in houses, in ditches, wherever there was cover. Pockets of enemy riflemen and machine-gunners were scattered in depth along the whole route of the advance. As our men pressed forward the fire came at them in front, from the sides, even from behind.

Fredd Carr wrote “Jerry would file out of houses with hands in the air, but we’d just mow him down. Strangely enough though, I, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, was just as bloodthirsty as the others. We had received orders to take no prisoners, not that we wanted to, and we left no wounded, we bayoneted those still living, it was a safety measure anyway.”

Eventually some New Zealanders made it to the edges of the runway but as sunlight rose and German resistance stiffing the attack stalled.

Coming into a village, 3 tanks engaged the enemy, a lead English tank was hit by a Bofors killing its commander and gunner, wounding the driver and setting the tank on fire. It’s driver managed to retreat and put out the fire. The second tank turned to avoid a 109s strafing run and hit a bamboo clump and broke a bogey wheel. The third tank was ordered to not go alone and such tank support for the mission ended.

It was 7 am by now, and casualties were mounting gravely. With Germans established in buildings and behind walls, any movement in the open became more and more hazardous.

The 28th Maori Battalion did how ever push on, George Dittmer at one point found his men forced to grown by enemy fire. “Call yourself bloody” soldiers and the attack went on until eventually strong enemy resistance at Hill 107 forced them to withdraw.

They had done their best, but Burrows had feared it was hopeless from the start. Now he knew that nothing more could be done.

By 10pm that night the stricken 20th had fallen back into a perimeter in the hills where the disappointed Maoris had also taken up defensive positions. There they sat within sight of the aerodrome, but unable to reach it with fire, watching the troop-carriers running a shuttle service between Maleme and Greece. Thousands more men were landed on Crete that day.

New Zealand soldiers advance across exposed ground during a failed counter-attack against German positions near Maleme airfield.

James Thomas Burrows

Charles Upham

Fighting Withdrawal

New Zealander Sandy Thomas recalls “We withdrew under orders soon after midnight carrying our wounded along a difficult clay creek bed to the road. Then we marched to nearly dawn, Everyone was tired, All were vaguely resentful, although non of us could put a finger on the reason.” Roy Farren recalls watching the Maoris coming back. “As they passed, they winked and put up their thumbs. They had not been beaten and they knew it. They had fought like tigers. The Maoris had executed one bayonet charge after another and they knew they were more then a match for the Germans. The surprise and the shame of the retreat was written on all their faces.”

There was a small battle for Platanias Bridge and the New Zealanders held off the Germans by mortars and some artillery fire. But this was just a delaying action as the Anzacs were being withdrawn to Galatas.

The Battle of Galatas

Early in the day all troops were warned that a massive enemy attack must be expected. The front line was held by the 18th Battalion. By four o’clock in the afternoon the Germans were ready to make their assault. The mortar fire increased, hundreds of bombs crashing down on the thin New Zealand lines. And into the dust and torn air thirty Stukas came screaming, adding their dive-bombing to the onslaught. Forward then came the German infantry, into the ranks of Kiwis who were already dazed and shattered. Under sheer pressure of lead and fire the right flank of the 18th was overwhelmed.

The Germans moved around the edges putting Galatas under siege with the line wavering John Gray commanding the troops in the thick of it went forward yelling, “No surrender, No surrender.” the men rallied for a short time before hundreds of New Zealander broke and ran.

A New Zealander wrote “ So I took off too and never ran so hard in my life before.”

Sir Kippenberger then moved among the panicked mob shouting “Stand for New Zealand” and “Stand every man who is a solider.” with such calm resolve that it stopped the defence disintegrating all together. With two sergeants he rallied the men to form a new line.

By nightfall the Germans rapidly swarmed into Galatas and set up in the little houses and put guns around the town square. Here was a dangerous lodgment which Kippenberger recognized increased the predicament of the New Zealand Division. It was too late now to attempt merely to patch the line; the risk before him was that everything might crumble away if the enemy were left in Galatas.

Kippenberger decided that he must strike, and strike boldly. Two British tanks were handy, one commanded by the notable Roy Farran, and two companies of the 23rd Battalion came up, tired but in good heart.

Kippenberger told the two companies that there was no time for reconnaissance; the tanks would move in, the infantry would follow in behind the tanks, single file on each side of the road, and take everything with them.

Now there were odd stragglers also joining in, glad to be given the chance of hitting back, linking themselves up to the two queues waiting on the roadside. There were groups from the 20th, some men of supply units, a few British officers, and all sorts of scattered remnants who refused to be left behind. In the very face of collapse and near-disaster, with men broken and exhausted, here was an example of resilience that was an inspiration.

It began at a walk, soon the men broke into a run to keep up with the tanks. And then, as the buildings of Galatas loomed up 200 yards ahead, there suddenly arose a clamour from the throats of men that still rings in the minds of those who heard it.

“The whole line seemed to break spontaneously into the most blood-curdling shouts and battle-cries … our chaps charging and yelling….’ ‘One felt one’s blood rising swiftly above fear and uncertainty until only an inexplicable exhilaration quite beyond description surpassed all else, and we moved as one man into the outskirts.”

LT Roy Farrans tank is knocked out as it entered the town square. He gets out and take cover behind a stone wall. He recalls New Zealanders came up the main street in a yelling rush, charging at Germans with bayonets and grenades. Slumped by the wall Farran shouts “Come on New Zealand! Clean ‘em out, New Zealand!”

Into the town they charged, along the lanes, over the walls, through the gardens, in and out of the buildings, shouting, fighting, and always driving forward. They were fired on from all sides, from roofs, doorways, and windows. They died quickly and freely, but the rest forged on. The noise was overwhelming. The enemy drew back, darting out of the houses and shops, trying to re-form on the far side of the village square. But there, even with our two tanks knocked out, another charge was thrown in. The Germans broke and ran.

There were scenes of great gallantry. Men raced straight into the face of enemy guns, plunging into the horrors of bayonet fighting with reckless heat, routing out the Germans with a fury that comes to those who have had to defend too long.

By midnight the town had been regained

A final massive counter-attack against the Germans was discussed during the night hours. But there were no fresh troops to make it, none who could be spared from the necessary task of merely delaying the inevitable. Crete was already lost. The commanders now had to prevent disaster.

So from courageous Galatas, out on a lonely but defiant limb, the men were spirited away before daylight, and brought back to the ridges just east of Karatsos, where they turned again, their backs now barely a mile from Canea. Here they would fight again.

Sir Howard Kippenberger with Charles Upham

Lieutenant Roy Farran

Brigadier John Gray

‘The troops under my command here have reached the limit of endurance. No matter what decision is taken by the Commanders-in-Chief, from a military point of view our position here is hopeless. A small, ill-equipped, and immobile force such as ours cannot stand up against the concentrated bombing that we have been faced with during the last seven days … the troops we have are past any offensive action.’ Lieutenant-General Bernard Cyril Freyberg. 26th May 1941, Crete

Battle of 42nd Street

Depleted New Zealand battalions, joined by the Australian 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions, withdrew towards Canea. All were weak, many down to less than half strength. By 27 May the survivors occupied a line running south from Suda Bay called 42nd Street. As the Anzac units reorganized a runner from the Australian unit asked for the New Zealand intention if the enemy broke through. Told of the decision to counter attack, the runner soon returned with the message “Wait a little and the Australians will be pleased to join you.”

Soon enemy forces made their appearance, driving swiftly eastwards. On the spot, the unit commanders decided that there was no future in quietly letting the enemy build up in front, and that it was futile thinking they could stem an enemy assault.

Hemara Aupouri from the 28th Maori Battalion clutching a Bren gun magazine like a club began to do the Haka, shouting a challenge. the Maoris next to him joined in and the started yelling. Ka mate! Ka ora! Ka ora! (I may die! I may live!) then a call to fix bayonets when out along the line.

The Maoris of 28th Battalion began it, most witnesses agree. They had watched the Germans coming, the efficient, almost contemptuous, drive of a victorious army. Bayonets fixed, they waited behind the walls and in the ditches.

Forward went the Maoris ‘with an élan almost incredible in men who had already endured so much’ (so wrote one historian). Within seconds they were followed by the 21st Battalion, the 19th, the 22nd, the 23rd—such of them as still remained. The haka had set the tone.

Here was something that baffles description. Men who were battered into defeat and exhaustion, with nothing left but rifles and bayonets, almost as one rising to their feet, hearing the shouts of their comrades, and taking the battle straight into the face of the enemy.

It was a scene of mass reaction—like the way a hush will suddenly fall over a huge crowd or the emotions of a thousand men will suddenly and simultaneously erupt as if spiritually controlled. They all went forward, walking grimly at first, then running, firing at the grey uniforms in the grass, behind the trees and hedges, using the bayonet ruthlessly on those who resisted. It was no panic charge of a distraught rabble. Officers kept the men to their senses, keeping interval to save casualties; but on and on they went. The uproar swelled over the peaceful fields of Crete.

For the enemy, the sight of troops advancing into the fire with such sharp pugnacity was too much. They fought for a moment, wavered, then fled. And they were destroyed as they ran. In a spirit of exhilaration for which there can be no words, our men swept the Germans back from 42nd Street nearly half a mile.

Johnny Peck an 19 year old Australian recounts. “Hand to hand combat was very frightening. you knew without a doubt that if you made a fraction of a mistake then you’re dead.”

Eventually the attack stopped and the Anzac troops fell back again to 42nd street. The attack had been a complete success. Our own casualties were surprisingly light. For the enemy it was a sad day. The 1st Battalion of 141st Regiment, fighting its first engagement, was all but eliminated, and other units were sharply cut about.

Hemara Aupouri

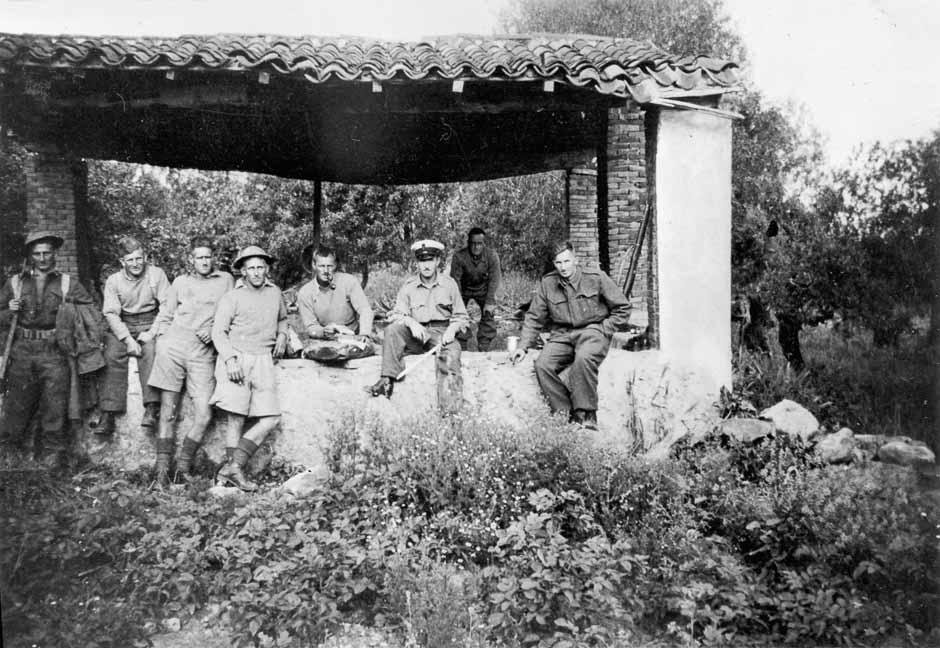

The Retreat to Sfakia

Evacuation had been ordered. A little fishing village on the south coast, called Sfakia, was the only place left from which the Navy could take men away. It was to be another Greece—another race between ships and enemy—another gamble as to how many men could be lifted from the beaches at night before the Germans arrived.

The road to freedom

It was a march of some forty miles to the south coast. The road seemed to lead upward all the way, with interminable zigzags, hairpin bends, and over mountain ridges reaching 3000 feet. To men who were fresh and fit this would have been a physical effort of some magnitude. But to the Kiwis, Australians, and British troops who were exhausted from lack of sleep, short of food and water, defeated by the weight and shock of never-ending air attack, whose courage had been futile in the absence of adequate fighting equipment, here was the culminating ordeal. To fall behind was to be taken prisoner. To continue ahead was to drive the body to unattainable lengths of endurance. The road was littered with abandoned equipment of all kinds. The dead lay there too. The wounded, the weak, the ones who fell out, lay with them. Some even struggled onwards on hands and knees.

D. M. Davin, writes ‘Trucks would pass ruthlessly along the column, ignoring the appeals of wounded men who would not fall out while their legs assured them that they might still be free. Or sometimes a truck would stop and one of its occupants would gruffly get out to make room for a man on foot whose condition was so bad that the passenger could not bear to ride while he walked. And of those who marched some went stonily on, ignoring the appeals of companions who could go no further; while others showed an awareness of something greater than their own exhaustion and did their best to struggle forwards, a wounded companion slung on a blanket or a wooden stretcher between them. And time and again the sight of a man stumbling along with an arm around the neck of each of two comrades who took turns carrying his rifle stressed its echo of Calvary.’

So in the course of several days thousands of the beaten Allies converged on Sfakia. While the Navy worked like demons to take them off, necessarily by night, they lay up in the caves and the stony gullies that ran sharply down to the rocky coast. As they waited their turn, the enemy came closer and closer.

Daniel Marcus Davin and his wife

The Evacuation begins

On the first night only 724 men were evacuated many of them walking wounded. At this point Discipline had collapsed and panic had taken over. It got so bad a cordon of troops with fixed bayonets around around the beach to keep the lanes open and control the unattached pushing desperately to get of Crete. Arthur Midwood, a Māori solider from Rotorua that had secured a spot on a evacuation ship recalls “I had difficulty getting on top because my arm was in a sling and I could only use one arm. I held on by the back of my head while i grabbed another rope. I got on board and crawled two meters across the deck and stayed there.” The second night was more successful. 6,000 men were evacuated including 550 wounded. The third night of evacuations was not ideal, of the 4 destroyers despatched only two arrived with one being damaged by air attack and another with mechanical problems. As a result some men were told they wouldn’t getting evacuated that night. Major Jim Leggat recalls “No one spoke for awhile and then we just rolled our pipe tobacco in our newspaper cigarette paper.” George Dittmer argued that all should go or non at all. He was overruled by his superiors with each company commander to nominate who would stay behind. Volunteers exceeded that number.

The rearguard meanwhile were holding the approaches to Sphakia. The German units engaged the defenders but found themselves up against infantry supported by tanks and artillery. He called for Air support but the Stukas had been sent to Poland.

Patrols were sent out by the Germans and they managed to come extremely close to temporary HQ in the caves. With startling suddenness, the sound of firing came to them from the direction of the ravine, only a few hundred yards away. The Allied rearguard was out holding the main approach road to Sfakia, some miles away. But now the enemy were within the perimeter.

One of those men responding to the German attack was Charles Upham ‘Get your men up there, Charlie!’ he called, pointing to the precipitous hills. ‘Get on top of them. And you’d better move fast.’ Upham looked at him. He was shrunken with illness, weary beyond description, still unable to eat, his wounds a dull heavy drag on his determination. But there was a shadow of a grin on his face as he said: ‘Oh, tell ’em to go to hell and not get excited.’ He turned to Dave Kirk beside him. ‘Get the boys moving, Dave. And tell ’em it’s a five-minute job.’ With his men worn out, himself driven by little more than will-power, Upham led the way up the face of the hill. When they eventually got in position the Germans were hopelessly caught by the plunging fire, the Germans ran desperately about, but they were doomed. One after another they fell to the fire sweeping down on them from overhead. Of the fifty Germans who came down the ravine that day, twenty-two were killed by Upham’s men. The rest were mopped up by other troops surrounding the valley. Later that night Charles Upham was evacuated under sticked orders he was not allowed to stay and a solider had to watch over him to make sure he got on the vessel. The order had come from Howard Karl Kippenberger.

That night a further 1,500 troops were evacuated from Crete. New Zealand Peter Fraser was in Egypt and he proclaimed “it would be a crushing disaster for our country and its war effort if such a large number of our men fell into enemy hands.” At this point Winston Churchill got involved and told the navy deputy chief that 5,000 men could not be left behind without an attempt to save them. This was going to be the final evacuation. During that day Germans engaged the defenders with machine gun and mortar fire but did not press the attack. Only 3,500 men were to be evacuated leaving 5,400 behind.

At 11.30 pm the convoy arrived of shore. One Australian unit who was promised of the island was entangled in a mass milling panic stricken men. Johnny Peck wrote “Hundreds of stragglers were determined to get away and any price and bugger the arrangements and controls for an ordered embarkation, Now it was every man for himself and now there was chaos.” The maoris were the last to leave covered by the royal marines. nearly 4,000 men were evacuated that night. After four nights they had evacuated 12,000 men. Half as many were still on the shore.

“Shocked, shamed and humiliated to a state of abject misery, we milled about the tiny village of Sphakia.” remembers kiwi driver Peter Winter.

Jack Ulrick from New South Wales wrote “Well that’s just bloody lovely. Here the mob, they’ve cleared out, they’ve left us here and i think if the jerries has asked us then, we would have joined their flaming army.”

Over 6,000 men were left waiting on a single beach the area was covered in debris left by departing troops.

The most senior officer of the commonwealth forces in Sphakia, then marched up the mountain and surrendered to the Germans which came at a surprise to them who expected a couple more days of resistance.

Back on the beach the men were told they capitulated and soon the Germans arrived and rounded them up. The men were then marched over the hills they had retreated from which took them 3 days.

Peter winter wrote about his journey “The bodies of hundreds of compatriots lying unburied in the olive groves and at the road side, bloated, flyblown and obscene in the heat of day.”

For the men who didn’t surrender they wandered the countryside for a way off the island with many been helped by locals. Some made it of Crete to North Africa, Others hid and some were captured.

If you would like to learn more about the Anzacs on Greece I recommend the book Where the Flaming hell are we? by Craig Collie.

Left Behind